Georg Jensen silver from Denmark has a tactile quality all its own, probably because it is handmade. It gets only better with age.

Michael von Essen, the founder and curator of the Georg Jensen Museum in Copenhagen, tried to explain its appeal: “Once you have touched pieces of Jensen, you want to have them. The silver has a warmth to it, whether the style is 1900, Art Deco or modern.” Last year, the company Georg Jensen founded celebrated its 100th anniversary. Jensen, who was not a gifted businessman, would probably have been surprised.

Jensen (1866-1935) was the seventh of eight children, born into a working-class family living north of Copenhagen. As a child, he worked with his father, a grinder in a knife factory. When he was 14, the family moved to Copenhagen. There he apprenticed with a goldsmith and took art classes, eventually passing the entrance exam for the Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts.

After graduating in 1892, he tried to earn a living as a sculptor and art potter. He married and had several children. In 1901, he joined the workshop of a metalsmith, who acquainted him with the Arts and Crafts Movement. For extra money, he made jewelry, and it sold.

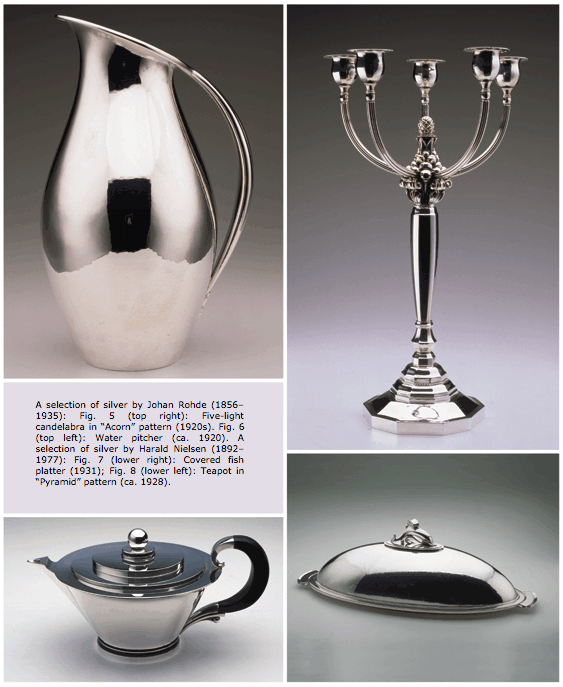

In 1904, with backing from a businessman, he was able to open his own workshop. A great craftsman, he took inspiration from Danish silver forms of the late 16th century, 17th-century Scandinavian baroque, Danish rococo and Art Nouveau. He created flatware and holloware: bowls, pitchers, tea sets, vases, even solid silver chandeliers. He always believed in silver as a material, for its affordability (vis-à-vis gold) and its intrinsic qualities.

“Silver is the best material we have,” Jensen said in an interview in 1926 on his 60th birthday. “Gold is precious for its worth, not for its effect. Silver has that lovely glow of moonlight, something like the light of a Danish summer night. Silver is like dusk, dewy and misty. Gold, on the other hand, is effective only in its brilliance and that it conceals much.”

Inspired by his childhood love of nature, Jensen designed services adorned with grapes, pine cones, blossoms and berries, which are still popular today. He employed people with different sensibilities, Deco to modernist, and, amazingly, let them initial their work.

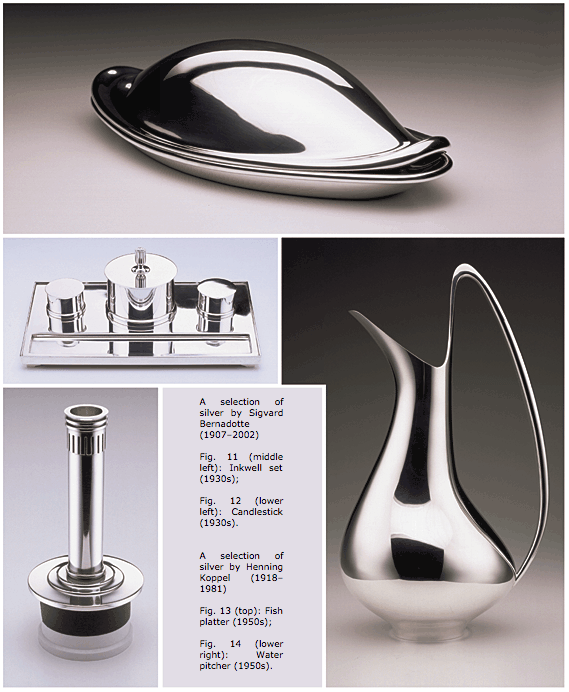

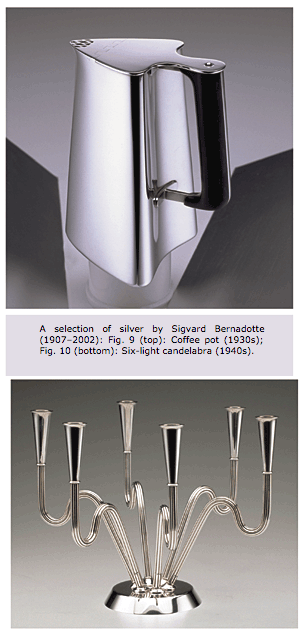

In 1931, for example, he hired Sigvard Bernadotte (1907-2002), the son of Gustaf VI Adolf, the king of Sweden. Bernadotte, the first to design exclusively in the modernist idiom, said his preference for simplicity was a reaction to Jensen’s own style. The prince remained there 50 years.

Beginning in 1909, Georg Jensen opened outlets in Berlin, Paris, London, Buenos Aires and, in 1924, New York. “For years, the shop was one of the most exquisite on Fifth Avenue,” Mr. von Essen said. “It was still important in the 1950’s, when it became a haven for everything Scandinavian.” Today, Jensen boutiques are on Madison Avenue and in SoHo.

On Wednesday, Christie’s New York is having what it claims is the first-ever auction devoted solely to Georg Jensen silver, with some 800 objects. Estimated to total $3 million to $5 million, the sale is titled the “Rowler Collection” after the name of the owner’s country estate in England, which Christie’s is also selling.

Erwin Eisenberg, an Israeli businessman based in London, is believed to be the consignor (as he wished to remain anonymous Christie’s would neither reveal nor confirm his name). In a telephone interview in which he declined to identify himself, the consignor said he began buying Jensen in 1996 and is selling it because “I have come to a time in life when I want to move on.”

He never intended to collect Jensen. “It was a bit of an accident,” he said. “I had an Art Deco dining table and needed some silver for it. Jensen is very livable silver. It wasn’t so recognized then and could still be bought cheaply. I found pieces in Argentina, Chile, Mexico and all over Europe.”

Mr. von Essen, the curator, who is giving a talk about Jensen on Monday at Christie’s, said: “The collection has incredible width in that it covers 100 years. Most people specialize in one period.”

Michael James, director of the Silver Fund, a London-based gallery that specializes in Jensen estate silver, estimated that “more than 50 percent of Jensen’s original production designs are in the sale.” Mr. James helped the consignor locate items when he was acquiring the collection. “Many of these pieces have never been at auction; they came from private dealers, estates and individuals,” he said.

“You can’t be everywhere, and you can’t get all the catalogs,” the owner explained. “The Silver Fund looked out for me. Many items were in private homes and had to be carefully sourced.” The Silver Fund also made the owner custom wooden cases for his Jensen flatware services; in the sale, they come with their contents.

Some of the consignor’s collection is illustrated (but not identified) in a 2003 book published by the Silver Fund: “George Jensen Holloware, the Silver Fund Collection” by David A. Taylor and Jason W. Laskey.

The sale has both popular designs and rare items, including a seven-light silver chandelier from 1920, a toothpick holder, a grape stand complete with grape scissors, and a gypsum model for an eel dish.

Modernists will appreciate the sleek Deco pieces, particularly a cylindrical tobacco canister designed by one of Georg Jensen’s sons, Jorgen Jensen. The pristine canister sits on little feet in the shape of a Z and is devoid of ornament. It is estimated at $5,000 to $8,000.

One memorable Arts and Crafts example is a silver and carnelian sugar caster that Jensen made for the Danish architect Anton Rosen in 1908. Based on a 1901 Rosen design for a heating stove, it was a collaboration. On the top, tigers march through a field of sugar cane, a hint at the purpose of the vessel.

“This sale has all the greatest hits,” said Jeanne Sloane, a silver specialist at Christie’s. “We think of Jensen as traditional, but many of the designers were avant-garde. Think of Verner Panton.” Panton (1926-98), the industrial designer known for the “Wire-Cone Chair,” worked with Jensen in the 1980’s.

Janet Drucker, a New York dealer who has specialized in Jensen for 27 years, would not say if she had sold to the consignor.

“The sale has some very rare pieces,” she said, “but I have never viewed people as collectors who buy something and then sell it all after only a few years. On the other hand, the sale has the aura of a celebrity auction. It may bring in new buyers.

“This is not ‘dated’ material,” she added. “It doesn’t have a ‘circa’ stamped on it. It’s appropriate for a modern house or a Deco home. I now have more young people registering for vintage Jensen flatware services on my bridal registry than ever.”

Michael James of The Silver Fund in New York City with what may be the most monumental sterling-mounted French furniture of the Twentieth Century: an Art Nouveau meuble d’appui by Jansen, circa 1905. Once owned by Jay Gould and auctioned at Sotheby’s in 1983, the cabinet was $450,000.

Michael James of The Silver Fund in New York City with what may be the most monumental sterling-mounted French furniture of the Twentieth Century: an Art Nouveau meuble d’appui by Jansen, circa 1905. Once owned by Jay Gould and auctioned at Sotheby’s in 1983, the cabinet was $450,000.

Besides his gift as a prolific designer, Jensen acted as mentor, encouraging other designers within his shop to create original silver designs, all the while overseeing production and training new employees. Perhaps more importantly, he gave designers full credit for their contributions in the company’s success, and each designer’s hallmark appears beside the Jensen hallmark on completed pieces. As a result of such support and encouragement, Jensen is lauded for helping Danish silver gain the international respect it continues to enjoy. In the decades since Jensen’s death in 1935, many talented designers have continued to create jewelry, hollowware, and flatware for the company. This fact was underscored in the Smithsonian Institution’s 1980 exhibition, Georg Jensen Silversmithy: 77 Artists, 75 Years.

Besides his gift as a prolific designer, Jensen acted as mentor, encouraging other designers within his shop to create original silver designs, all the while overseeing production and training new employees. Perhaps more importantly, he gave designers full credit for their contributions in the company’s success, and each designer’s hallmark appears beside the Jensen hallmark on completed pieces. As a result of such support and encouragement, Jensen is lauded for helping Danish silver gain the international respect it continues to enjoy. In the decades since Jensen’s death in 1935, many talented designers have continued to create jewelry, hollowware, and flatware for the company. This fact was underscored in the Smithsonian Institution’s 1980 exhibition, Georg Jensen Silversmithy: 77 Artists, 75 Years.